Secure software updates

Security is a process and isn’t enough to reliably boot the operating system version installed at the factory—there must also exist a mechanism to quickly and securely obtain the latest security updates. Apple regularly releases software updates to address emerging security concerns. Users of iPad and iPhone devices receive update notifications on the device. Mac users find available updates in System Settings (macOS 13 or later), or System Preferences (macOS 12 or earlier). Updates are delivered wirelessly, for rapid adoption of the latest security fixes.

Update process security

The update process uses the same hardware-based root of trust that secure boot uses that’s designed to install only Apple-signed code. The update process also uses system software authorization to check that only copies of operating system versions that are actively being signed by Apple can be installed on iPad and iPhone devices, or on a Mac with the Full Security setting configured as the secure boot policy in Startup Security Utility. With these secure processes in place, Apple can stop signing older operating system versions with known vulnerabilities and help prevent downgrade attacks.

For greater software update security, when the device to be upgraded is physically connected to a Mac, a full copy of iOS or iPadOS is downloaded and installed. But for over-the-air (OTA) software updates, only the components required to complete an update are downloaded, improving network efficiency by not downloading the entire operating system. What’s more, software updates can be cached on a Mac with macOS 10.13 or later with Content Caching turned on, so that iPad and iPhone devices don’t need to redownload the necessary update over the internet. (They still need to contact Apple servers to complete the update process.)

Personalized update process

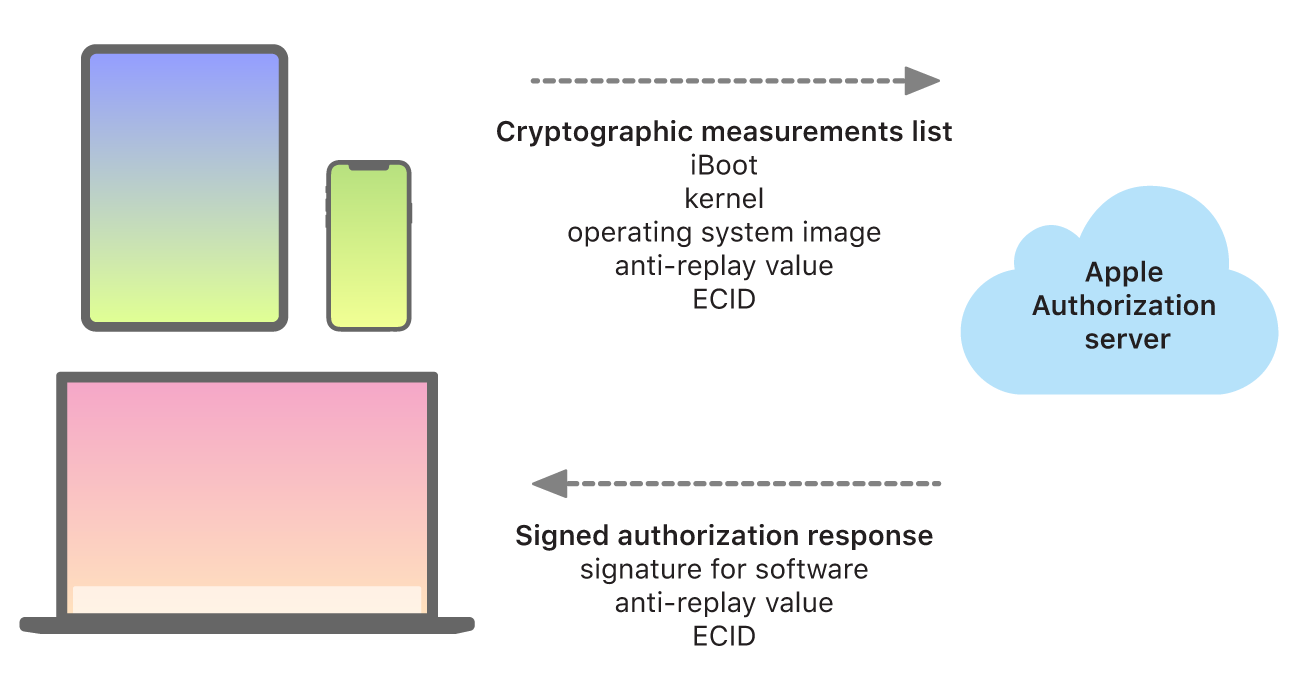

During upgrades and updates, certain information is made available to the Apple installation authorization server, which includes a list of cryptographic measurements for each part of the installation bundle to be installed (for example, iBoot, the kernel, and the operating system image), a random anti-replay value, and the device’s unique Exclusive Chip Identification (ECID).

The authorization server checks the presented list of measurements against versions whose installation is permitted and, if it finds a match, adds the ECID to the measurement and signs the result. The server passes a complete set of signed data to the device as part of the upgrade process. Adding the ECID “personalizes” the authorization for the requesting device. By authorizing and signing only for known measurements, the server helps ensure that the update takes place exactly as Apple provided.

The boot-time chain-of-trust evaluation verifies that the signature comes from Apple and that the measurement of the item loaded from the storage device, combined with the device’s ECID, matches what was covered by the signature. These steps are designed to ensure that, on devices that support personalization, the authorization is for a specific device and that an older operating system or firmware version from one device can’t be copied to another. The anti-replay value helps prevent an attacker from saving the server’s response and using it to tamper with a device or otherwise alter the system software.

The personalization process is why a network connection to Apple is always required to update any device with Apple-designed silicon, including an Intel-based Mac with the Apple T2 Security Chip.

On devices with the Secure Enclave, that hardware similarly uses system software authorization to check the integrity of its software and is designed to prevent downgrade installations.