Logic Pro User Guide for iPad

- What’s new in Logic Pro 1.1

-

- What is Logic Pro?

- Working areas

- Work with function buttons

- Work with numeric values

-

- Intro to tracks

- Create tracks

- Create tracks using drag and drop

- Choose the default region type for a software instrument track

- Select tracks

- Duplicate tracks

- Reorder tracks

- Rename tracks

- Change track icons

- Change track colors

- Use the tuner on an audio track

- Show the output track in the Tracks area

- Delete tracks

- Edit track parameters

- Start a Logic Pro subscription

- How to get help

-

- Intro to recording

-

- Before recording software instruments

- Record software instruments

- Record additional software instrument takes

- Record to multiple software instrument tracks

- Record multiple MIDI devices to multiple tracks

- Record software instruments and audio simultaneously

- Merge software instrument recordings

- Spot erase software instrument recordings

- Replace software instrument recordings

- Capture your most recent MIDI performance

- Use the metronome

- Use the count-in

-

- Intro to arranging

-

- Intro to regions

- Select regions

- Cut, copy, and paste regions

- Move regions

- Remove gaps between regions

- Delay region playback

- Trim regions

- Loop regions

- Repeat regions

- Mute regions

- Split and join regions

- Stretch regions

- Separate a MIDI region by note pitch

- Bounce regions in place

- Change the gain of audio regions

- Create regions in the Tracks area

- Convert a MIDI region to a Drummer region or a pattern region

- Rename regions

- Change the color of regions

- Delete regions

- Create fades on audio regions

- Access mixing functions using the Fader

-

- Intro to Step Sequencer

- Use Step Sequencer with Drum Machine Designer

- Record Step Sequencer patterns live

- Step record Step Sequencer patterns

- Load and save patterns

- Modify pattern playback

- Edit steps

- Edit rows

- Edit Step Sequencer pattern, row, and step settings in the inspector

- Customize Step Sequencer

-

- Effect plug-ins overview

-

- Instrument plug-ins overview

-

- ES2 overview

- Interface overview

-

- Modulation overview

-

- Vector Envelope overview

- Use Vector Envelope points

- Use Vector Envelope solo and sustain points

- Set Vector Envelope segment times

- Vector Envelope XY pad controls

- Vector Envelope Actions menu

- Vector Envelope loop controls

- Vector Envelope release phase behavior

- Vector Envelope point transition shapes

- Use Vector Envelope time scaling

- Use the Mod Pad

- Modulation source reference

- Via modulation source reference

-

- Sample Alchemy overview

- Interface overview

- Add source material

- Save a preset

- Edit mode

- Play modes

- Source overview

- Synthesis modes

- Granular controls

- Additive effects

- Additive effect controls

- Spectral effect

- Spectral effect controls

- Filter module

- Low and highpass filter

- Comb PM filter

- Downsampler filter

- FM filter

- Envelope generators

- Mod Matrix

- Modulation routing

- Motion mode

- Trim mode

- More menu

- Sampler

- Copyright

Other waveform properties

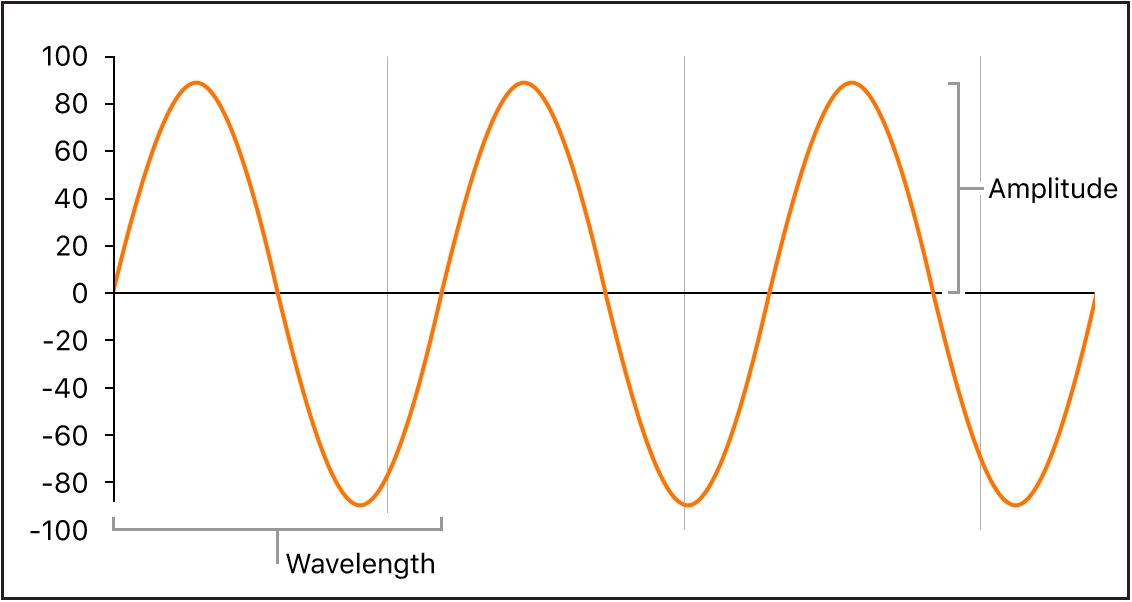

In addition to frequency, other properties of sound waves include amplitude, wavelength, period, and phase.

Amplitude: The amplitude of a waveform indicates the amount of air pressure change. It can be measured as the maximum vertical distance from zero air pressure, or “silence” (shown as a horizontal line at 0 dB in the illustration). Put another way, amplitude is the distance between the horizontal axis and the top of the waveform peak, or the bottom of the waveform trough.

Wavelength: The wavelength is the distance between repeating cycles of a waveform of a given frequency. The higher the frequency, the shorter the wavelength.

Period: The wave period is the amount of time it takes to complete one full revolution of a waveform cycle. The higher and faster the frequency, the shorter the wave period.

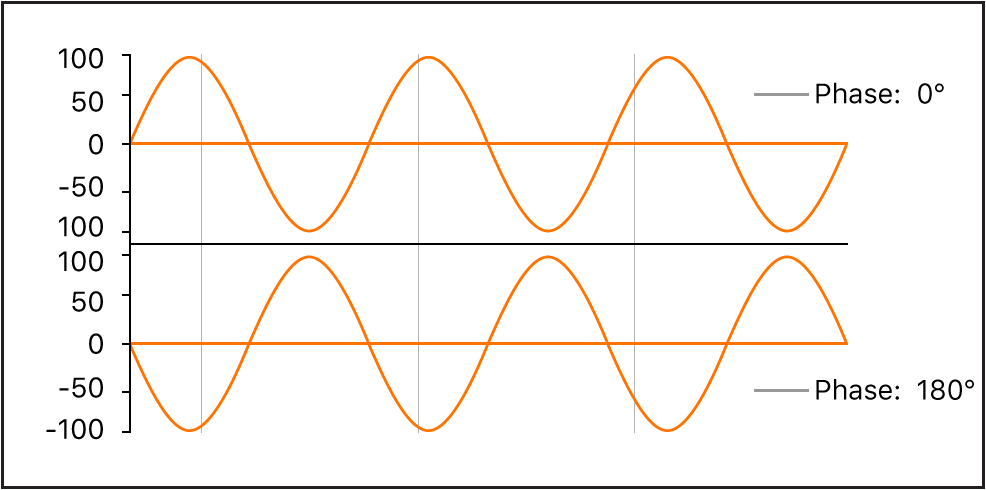

Phase: Phase compares the timing between waveforms and is measured in degrees—from 0 to 360.

When two waveforms begin at the same time, they are said to be in phase or phase-aligned. When a waveform is slightly delayed in comparison to another waveform, the waveforms are said to be out of phase.

Note: It is difficult to discern a constant phase difference over the entire wave period, but if the phase of one of the waveforms changes over time, it becomes audible. This is what happens in common audio effects such as flanging and phase shifting.

When you play two otherwise identical sounds out of phase, some frequency components—harmonics—can cancel each other out, thereby producing silence in those areas. This is known as phase cancelation, and it occurs where the same frequencies intersect at the same level.

Fourier theorem and harmonics

According to the Fourier theorem, every periodic wave can be seen as the sum of sine waves with certain wave lengths and amplitudes, the wave lengths of which have harmonic relationships—that is, ratios of small numbers. Translated into more musical terms, this means that any tone with a certain pitch can be regarded as a mix of sine tones consisting of the fundamental tone and its harmonics, or overtones. For example, the basic oscillation—the fundamental tone or first harmonic—is an “A” at 220 Hz, the second harmonic has double the frequency (440 Hz), the third harmonic oscillates three times as fast (660 Hz), the next harmonics four and five times as fast, and so on.

Download this guide: PDF